Beyond physical barriers and checkpoints, Palestinians in the West Bank contend with communications frequencies as an invisible infrastructure of control.

In a 2009 advertisement promoting the Israeli telecommunications company Cellcom, a group of soldiers is shown patrolling the West Bank’s separation wall in a military Jeep. The Jeep comes to an abrupt stop after a football suddenly flies over from the other side of the wall, landing on the hood of the vehicle. One of the soldiers picks up the football, inspects it, and then uses his cell phone to call for reinforcements before throwing the ball back to the other side. Against a digitally-rendered view of the separation barrier towering high in the background, the ad unexpectedly concludes with a growing crowd of soldiers cheering, laughing, and energetically playing football with an implied, but unseen, Palestinian.

Not surprisingly, the commercial caused widespread controversy. In its defence against Palestinian outrage at the ad’s lighthearted portrayal of a military occupation, Cellcom indicated that its intention was “to get the message across that when people separated by religion, race, and gender want to communicate, they can, under any circumstances.” The advertisement conceivably foreshadows the future conditions for the advancement, as well as the appropriation, of telecommunication infrastructure in the West Bank. But this infrastructure continues to legitimize new forms of control in the Palestinian territories — Israeli communication companies are strategically, and directly, involved in the unlawful occupation of the West Bank and Golan Heights. Perhaps the invisible football player depicted in the ad is not only an inference of a Palestinian child, but also of the shadows of Israel’s cellular infrastructure “at work deep inside” in the Palestinian territories.

The means of making a phone call in the West Bank are implicated in Israel’s tightening of geopolitical control over Palestinian lands: the expansion of settlements, settler-only roads and checkpoints, confiscation of land and equipment, and administration of technical systems have all become entangled with telecommunications. For instance, the uneven transmission of signals is evident in the asymmetrical advancement in technology and development of the built environment between Israeli and Palestinian territories. Blocking access to frequencies is a tactic deployed to prevent and suspend Palestinians from exercising their rights to use up-to-date technologies and improve urban conditions. As reflected in Cellcom’s advertisement, communication infrastructures in the West Bank remain both in the background and foreground: as a static representation of the compromised sovereignty of Palestinians, or a lived experience subject to colonial control.

Cellcom’s commercial also reveals the colossal, if sometimes metaphorical, cracks at which the telecommunication network is built. They are evident in the difference between visible infrastructure, constructed unevenly in the West Bank — satellite dishes, reception antennas, cables, walls, and roads — but also the invisible technical standards that operate invisibly as a mode of governance. These fissures are further deepened by the settler-colonial authority’s policies and regulations, obstructing supposedly neutral promises to connect “every Palestinian to the rest of the world.” However, the simple use of a cellular device — whether to text, call, connect via Instagram or any other social media app — reveals the underlying issues of digital infrastructure inscribed as a means of territorial control. The spatial fracture of the West Bank is multiplied by thousands of geographic cellular networks; Palestinians receive contingent coverage as a result of the ongoing physical and digital occupation.

The electromagnetic spectrum consists of radio wavelengths, frequencies, and photon energies whose features enshrine a porous landscape of cellular connection. To achieve connection, a cellular network is distributed over land areas referred to as cell sites. A local transceiver serves each cell, and each transceiver broadcasts information over radio waves. Radio propagates from one transceiver to another horizontally, recognising no borders; but signals are affected by the transceivers’ physical surroundings, from barriers, walls, and the built environment, to topographical differences in the landscape. Radio propagation is bound by governmental administration of frequencies, confining wavelengths to strictly calculated areas. Yet, the electromagnetic spectrum’s properties remain understood largely as the relational backbone of the built infrastructure. However, the agency of frequencies themselves needs to be confronted. Frequencies are sites of mediation, but also of domination and contestation. The electromagnetic spectrum is often overlooked as a spatial instrument and as a potential tool to imagine, organise, and control urban environments and their conditions.

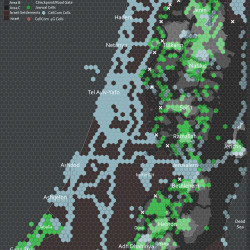

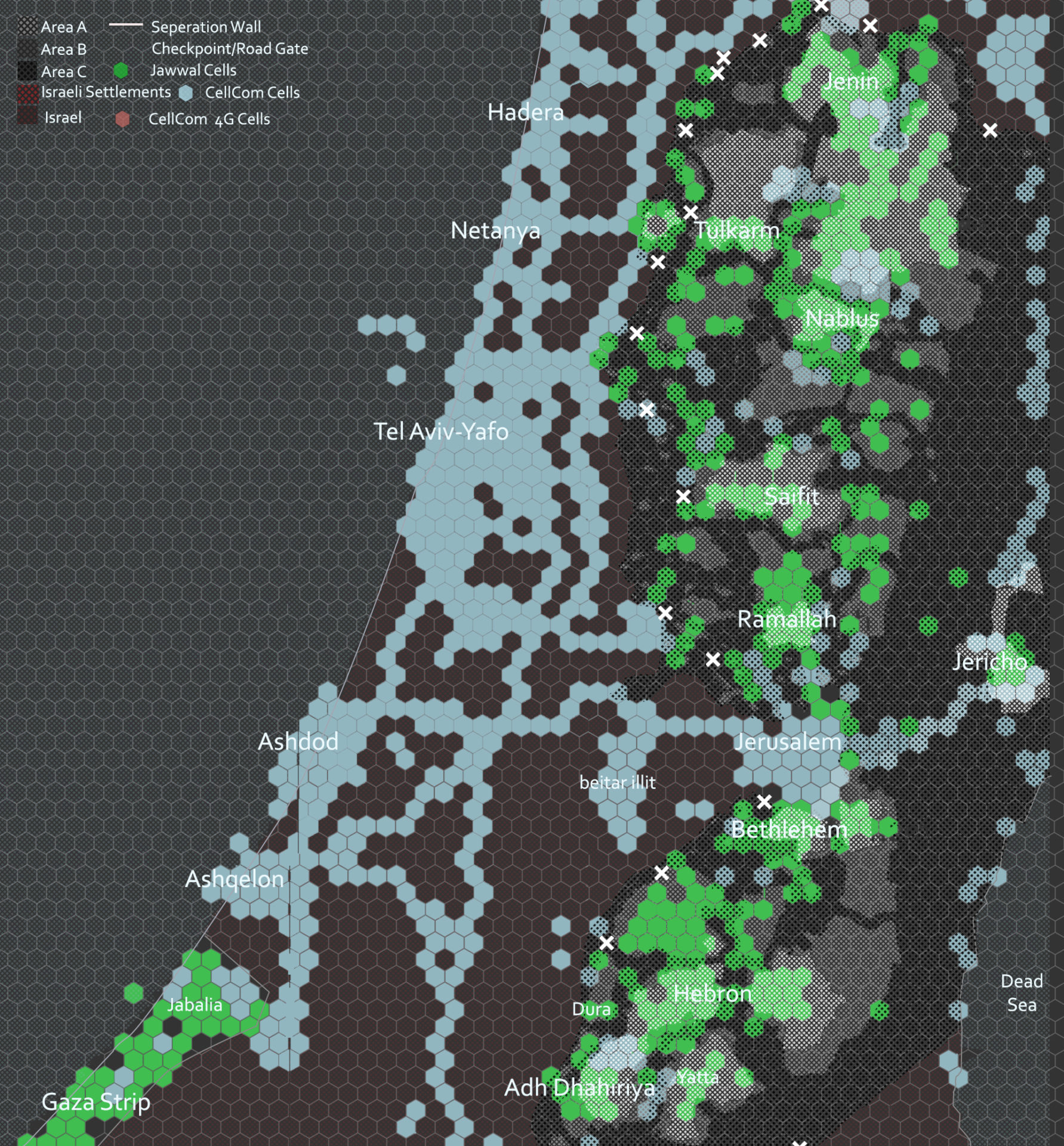

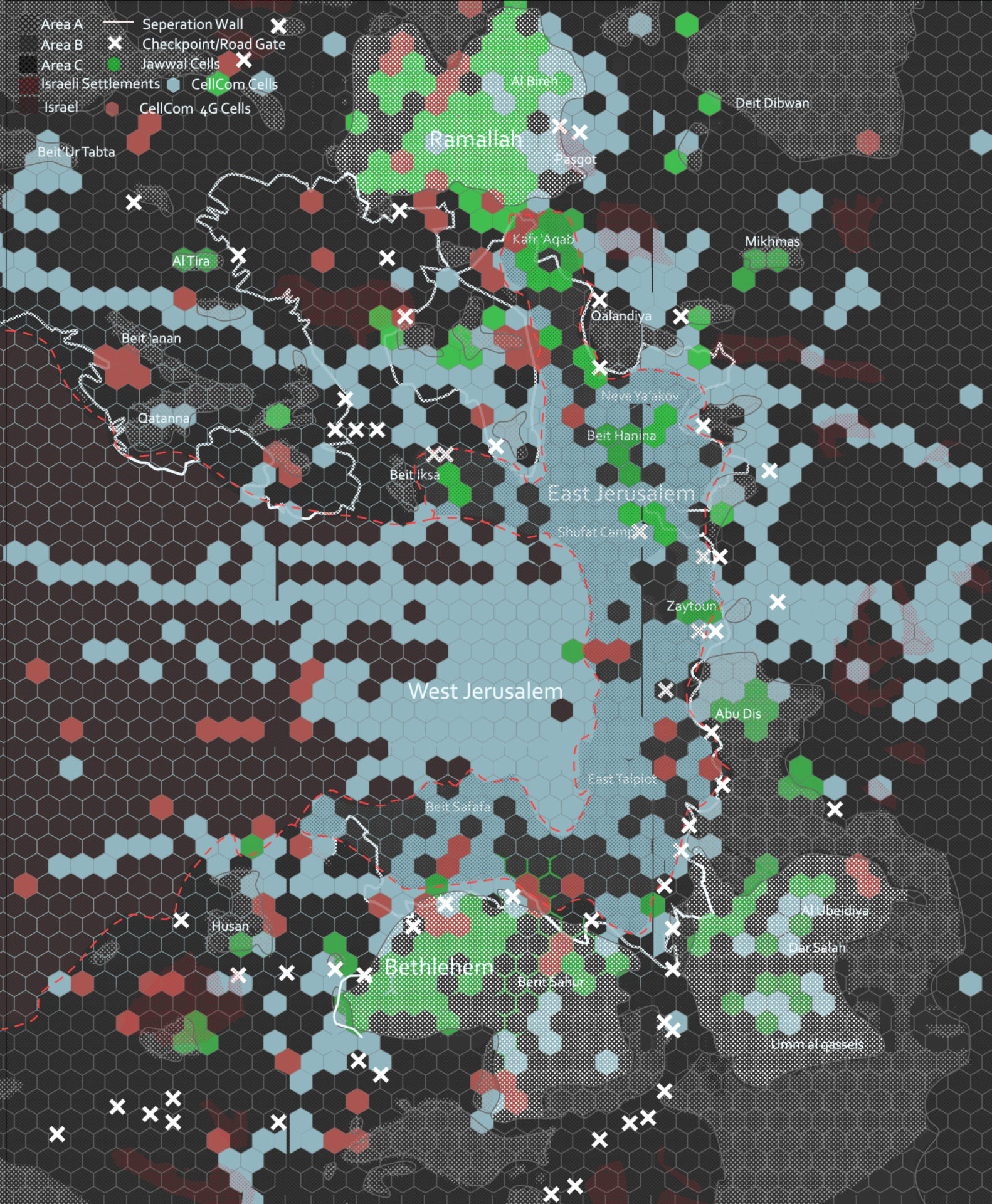

To map the spectrum’s utilities is to uncover how communication technologies are both expanding and constraining ways of inflicting violence, exposing frequencies as active tools in manifesting spatial control, and revealing how the spectrum is treated as what media scholar Helga Tawil Souri calls “a territorial asset.” As a result of the 1995 Oslo Accords, frequencies were distributed across the occupied Palestinian territories’ municipalities. Each city was provided with the electromagnetic backbone for developing its own telecommunication network: the ability to own and build its national TV channels, private radio channels, Global Systems for Mobile (GSM), and internet networks. These technologies formed new communication zones for each of the Palestinian regions, which should have facilitated the radical development of communication systems.

However, this potential was hindered by the spatial division of the West Bank into three areas: A, B, and C. In each area, the state of Israel has a tight grip on these revolutionary promises, restricting access to electromagnetic and radio frequency spectrums and denying Palestinian authorities the right to build submarine cables, satellite stations, optical fibres, and microwave systems. One spectator from a Hebron-based news broadcast in the West Bank commented about the politicisation of the spectrum, stating that “there is a vicious war being launched in the area of frequency.” On this account, the Israeli government’s practices are oriented towards enclaving cellular spaces as much as protecting, defending, and demarcating physical spaces.

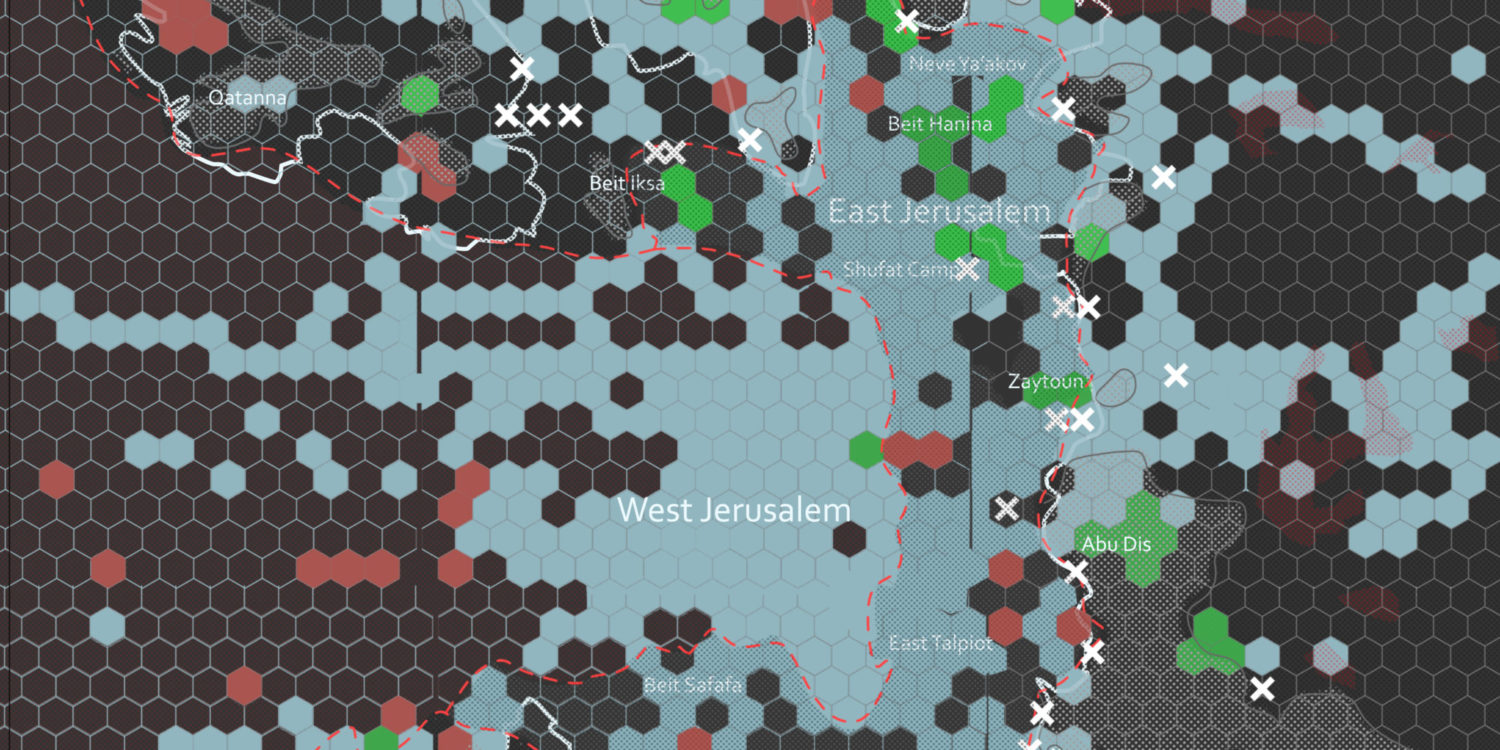

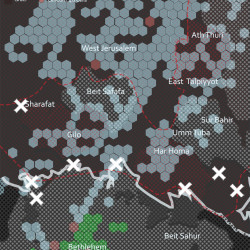

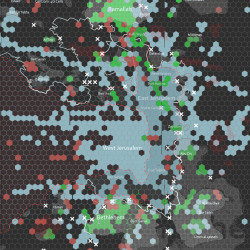

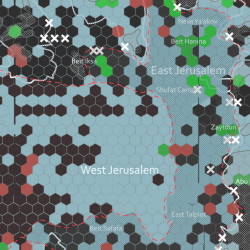

In the West Bank, 3G signals obey a particular spatial order; they follow the territorial demarcation and control imposed by the Israeli military. Cell phone coverage provided by the Palestinian national phone operator, Jawwal, is variegated. Frequencies and bandwidth conform to spatial fragmentation as informed by Israel’s juridical and political practices. Jawwal, the national cellular operator of the West Bank, is only permitted to connect to and have a strong cellular signal in Area A, which is exclusively administrated by the Palestinian Authority. Hence, the stability of receiving signals for a phone call fluctuates across the territories: the quality of a phone call will depend on the signal strength, the congestion according to the operator’s administrated frequency bandwidth, the state administration of the region, and the surrounding telecommunication infrastructure.

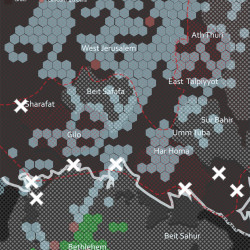

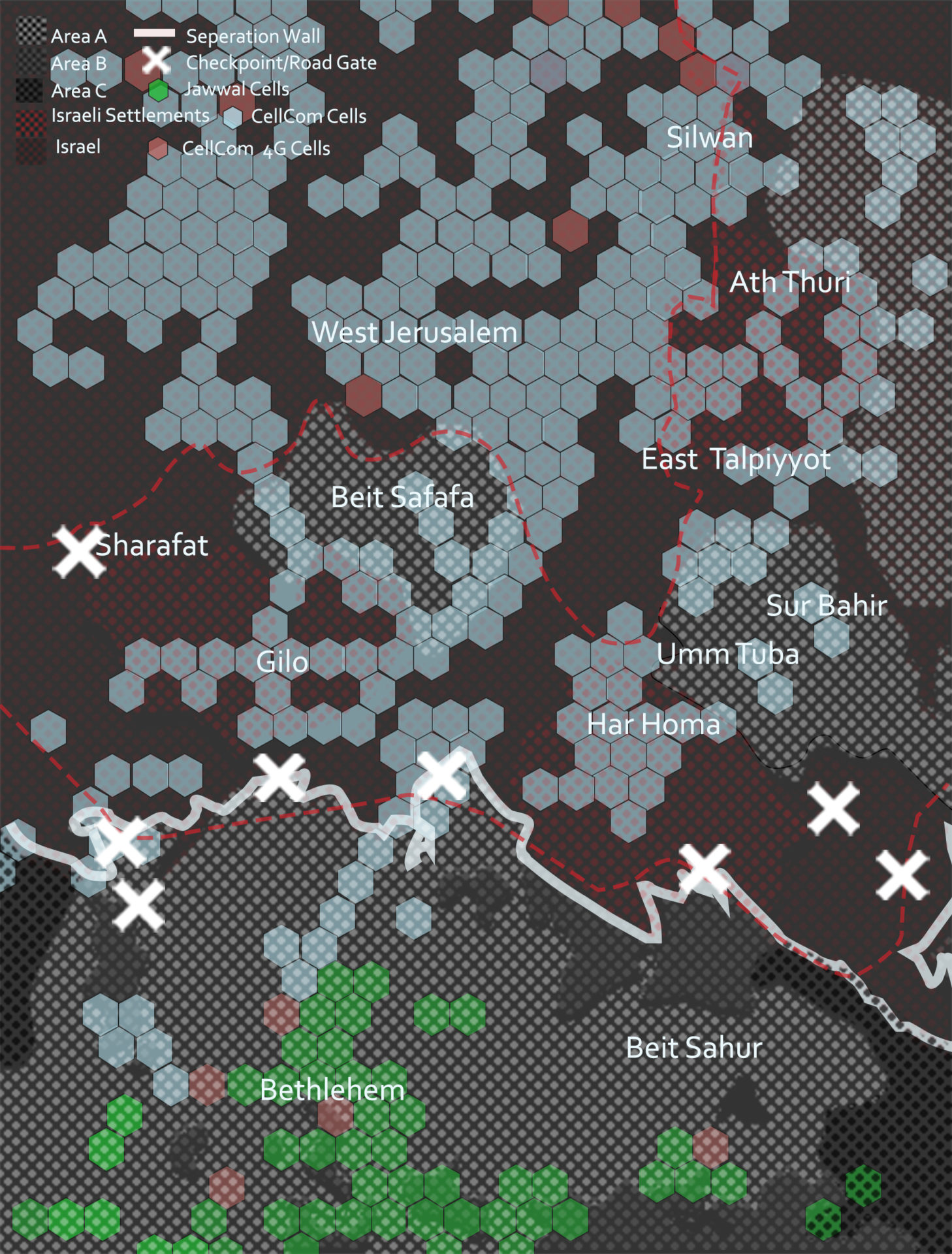

The lived experience of this telecommunication infrastructure reflects the uneven development of West Bank cities. For instance, Daoud Kuttab, media activist and general director of Community Media Network based in Jordan, stresses that buying multiple sim cards is a necessity for commuting throughout Palestine. Specifically, three sim cards from different national mobile companies are required: one from Jawwal, the leading cellular service operator in Palestine; another from Zain, the operator in Jordan; and a third one from Cellcom. Each sim card is used within a specific region. For instance, the Jawwal sim card is only useful in area A, and rarely in Area B, but not when bypassing Area C. Hence when Daoud crosses checkpoint 300 to go to East Jerusalem along the 600 roads, he is instantly off the cellular grid.

Therefore, at checkpoints that have constrained Palestinian mobility from one region to one another, Palestinian cell signals are also denied entry. These checkpoints, referred to as the “telephonic no-man’s-land” by Souri, are spaces of connection, but also equally of disconnection. They embody violent, disruptive, illogical systems of movement. Only two kilometres away from the separation wall, checkpoint 300 exemplifies the physical manifestation of containment and lived trauma: metal detectors, surveillance cameras, barricade fences, and security walls slow and suspend Palestinian movement, reflecting the depth and breadth of ways to secure spatial enclosure. Yet the spatial delimitation is also reproduced in cellular networks. A Jawwal subscriber would not receive any signal in these checkpoints, as the company cannot install any antennae, cables, or dishes near the area. To that end, a phone call, as Kuttab reminds us, is “political” — despite the de-territorialising processes associated with communication technologies, they are creating new spaces for new forms of occupation.

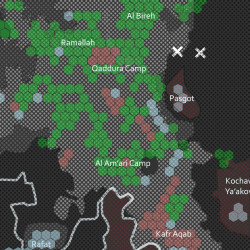

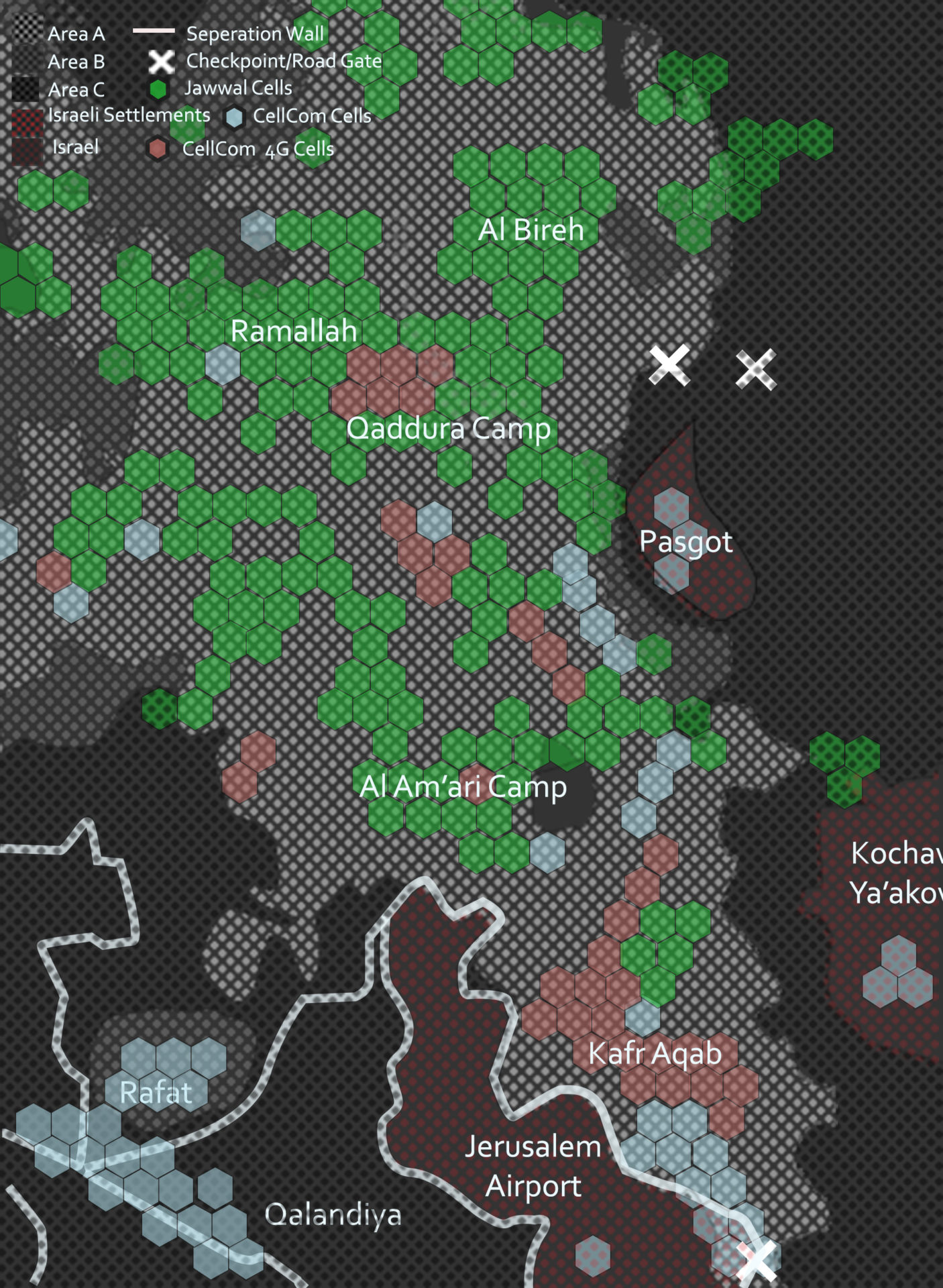

Meanwhile, in the centre of these Palestinian territories, frequencies echo the neoliberal aspirations of a nation-city. The de-facto capital of the West Bank, Ramallah, was proclaimed to be the first “smart city” in the Palestinian territories. One of the state’s many initiatives towards realising this vision is to build the municipality’s first Geographic Information System (GIS) platform. According to its director, the system intended for the management and reallocation of public infrastructure has “revolutionized the organization of data“. Yet despite these technological advancements, Ramallah lacks much of the necessary physical infrastructure to build, let alone become a “smart city”. For example, access to 4G and 5G frequencies is restricted by Israeli authorities who have not provided Jawwal’s cellphone service with the necessary bandwidth. However, this underlying issue was circumvented, with attention redirected toward addressing other ways of advancing the “smart city” end goal. Plans include installing fibre optics, and providing unlimited WiFi to fourteen municipal buildings, as well as two gigabytes of monthly WiFi to all landline telephone subscribers. Recently, the municipality installed cameras to regulate traffic flow, established a local alternative to Google Maps, and provided access to numerous GIS platforms available online.

Torn between political aspirations of becoming a technologically advanced city, and colonial occupation that has crippled its telecommunications capacities, Ramallah disguises these disparities in ethno-nationalist narratives. The hopes and aspirations of being a smart city are imbued with a national logic. Jawwal continues to position itself as the city’s nationwide image, dominating billboards, building façades and window shops, as well as hosting social events such as ‘Ana Jawwal’ (I am Jawwal) on campus universities. More and more people have subscribed to Jawwal driven by a sense of nationalism. At the same time, on the outskirts of the city lie illegally built Israeli settlements such as Migron and Psagot, constructed on a higher topography than Ramallah. These settlements overshadowing the city have highly advanced and securitised cellular antennas, illicitly built on private lands owned by Palestinian families. As noted by Helga, one Jawwal subscriber described that one should “only look up” to the surrounding hills to know why the Jawwal signals are weak.

This series of maps does not obscure and depoliticise the spectrum’s mechanisms. Instead, armed with the knowledge of the electromagnetic spectrum’s spatial and political impacts in the West Bank, we must find ways to reverse the unbalanced power of cartography, its representation, and imagination. These tools of representation must shed the shackles of traditional cartographies and engage with the actual physical realities on the ground. Moreover, this reversal should uncover how the conditions for communication — infrastructural nodes, the cellular networks, the transmission, and the strength of signals — are entangled with the territory’s materiality. Writ large, these complex relations should be registered in a critical understanding of the cellular landscape, revealing the spatial implications of a politicised electromagnetic spectrum, and of weaponised frequencies and wavelengths.

Cities After Algorithms

Cities After Algorithms is a content series exploring how algorithms generate and influence the spaces we live, work and move around in. Algorithms shape the city after their own image, but it is an image they have been trained to see. The tendency to mistake collected data for reality produces a self-fulfilling prophecy by leaving little room for intervention, experimentation or otherness. The more this technological determinism rules the use and design of cities, the more the city will be organised after mechanical parameters instead of socio-political ideals. The special series Cities After Algorithms is produced in collaboration with Failed Architecture, and is supported by the Dutch Creative Industries Fund.

Jumanah Abbas

An architect, a writer, and a researcher working between New York and Doha city. Jumanah received her master’s degree in Critical, Curatorial, and Conceptual Practice from Columbia University (2020) and her undergraduate degree in Architecture from American University of Sharjah (2018). Using architectural drawings, videos, and objects, her practice looks at how educational pedagogies and environments impact how different forms of knowledge circulate, as well as condition the urban landscape.